As a boy growing up in Alabama during the heat of the Civil Rights Movement, I was familiar with the name of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but only as a name in a news headline or a textbook. I was a child when the Freedom Riders’ bus was attacked by a hostile mob and burned a few miles from our home near Anniston. Weeks later, I remember sitting on a curb in front of Wikle’s Drugstore on Noble Street watching my first Civil Rights March. With grandparents who were avid Wallace democrats, I knew a lot about the governor from Clio, but very little about the man who marched in Selma. That is, until 1982.

During my senior year at Jacksonville State University, I participated in a field trip to Atlanta with the Sociology Club. We visited several sites of social and cultural significance including the Atlanta Federal Corrections Facility, the Grady Hospital, the Ebenezer Baptist Church and the King Center.

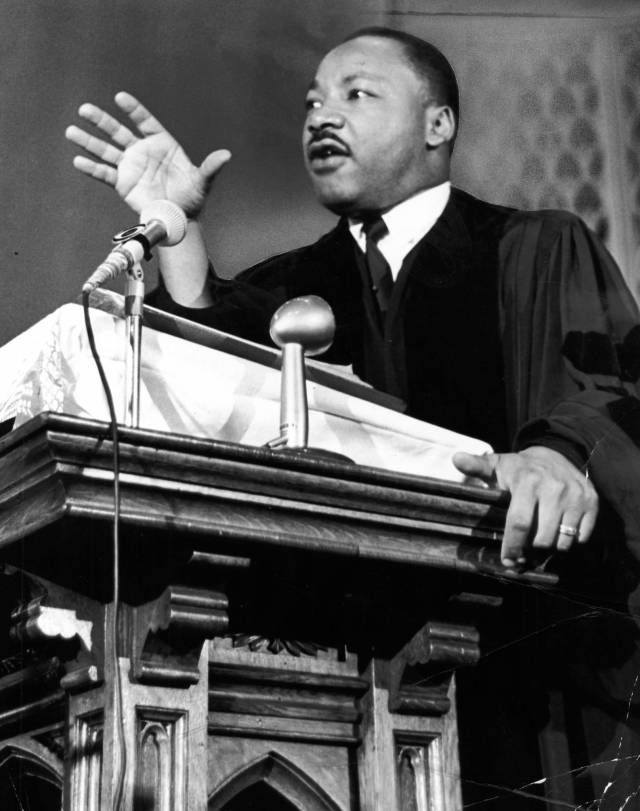

While touring the sanctuary of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, another student and I ventured into the pulpit and stood briefly where Dr. King had stood to preach. The hostess immediately reprimanded us, informing us that in their church tradition, only ministers of the gospel were allowed to “stand behind the sacred desk.” I relieved her sense of alarm by informing her that I was a “licensed” Baptist minister and that my friend was preparing to be an Episcopal priest, a claim which our faculty sponsor, Dr. Rodney Friery, confirmed for the hostess.

Upon learning of our ministerial affiliation, the hostess allowed us to take in the view from one of the most strategic pulpits in our nation’s history. Then she invited us to follow her to the King Center adjacent to the historic church where she led us through the Archives Area, and then through a door that was labeled “Authorized Personnel Only.”

Once inside, we discovered we were in an expansive storage facility with row after row of shelves containing hundreds of boxes. She took a couple of boxes from the shelves, opened them, and allowed us to view the contents. We quickly realized that the hostess was giving us the privilege of examining some of Dr. King’s personal sermon notes, and speeches, and correspondence. This information was being stored temporarily and would soon be processed for the archives.

The notes we scanned were mostly handwritten on hotel stationary, restaurant napkins, used mailing envelopes, and on the backside of “incoming” personal letters. While many respected orators labor intensively over manuscripts, revising multiple drafts in order to arrive at just the right script, it was obvious that Dr. King had a rhetorical gift for rendering a speech extemporaneously and passionately from a few scribbled notes.

After half an hour or so, our time was up and we rejoined the others in our group. Only years later have I come to realize the distinct privilege given to us that day in Atlanta. Since that time, I have read most of Dr. King’s published writings as well as many commentaries and editorials about Dr. King’s life and work.

Dr. King courageously pursued his dream of equal opportunity for all persons, and he employed and encouraged non-violent means to advance a course toward civil rights. The voice and vision from Dr. King’s pulpit helped shape a movement that began transforming our nation and our world, a movement that continues to this day. And we would do well to learn from his prophetic voice, his relentless pursuit of equality, and his strategy for nonviolent protests and peaceful resistance.

(Dr. Barry Howard serves as the Senior Minister at the First Baptist Church in Pensacola, Florida.)