In a world that praises hustle and rewards burnout, Jesus offers something profoundly countercultural: rest. Not the kind of rest you squeeze in between meetings or tack onto the end of an overbooked week, but real rest—the kind that restores the soul, quiets the mind, and invites us back into wholeness.

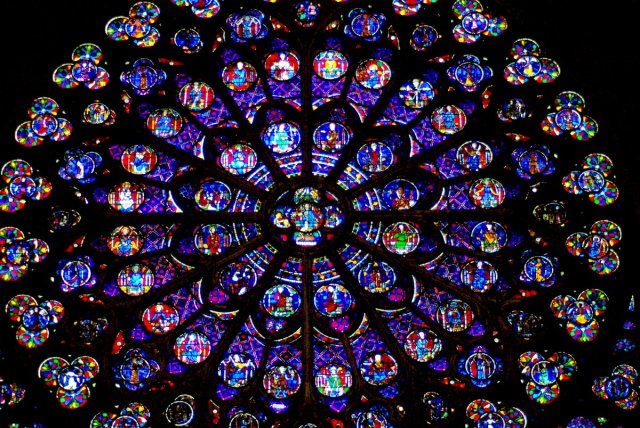

In Matthew 11:28–30 (The Message), Jesus extends an invitation: “Are you tired? Worn out? Burned out on religion? Come to me… Walk with me and work with me—watch how I do it. Learn the unforced rhythms of grace.”

These words, so aptly paraphrased by Eugene Peterson, feel less like a command and more like a gentle hand on the shoulder, drawing us toward something better than exhaustion: grace.

Learning to Rest Is a Strength, Not a Weakness

In her book Invitation to Silence and Solitude, Ruth Haley Barton writes, “Because we do not rest, we lose our way… Poisoned by the hypnotic belief that good things come only through unceasing determination and tireless effort, we can never truly rest.”

It’s easy to assume that if we stop, we’ll fall behind. But Jesus flips the script—he teaches that rest is not an interruption to spiritual formation; it is spiritual formation. It’s how we learn to hear his voice above the noise.

A Gentle Yoke in a Demanding World

Jesus invites us to “take his yoke”—a farming tool once used to link animals for shared work. But his yoke isn’t burdensome. It’s custom-fit, gentle, and shared. We don’t pull alone. We’re yoked with Christ, walking in step with his grace.

Years ago, I met a retired pastor who had served faithfully for five decades. When I asked him his secret to longevity, he said simply, “I finally learned to walk at God’s pace.” That’s what Jesus means by unforced rhythms—it’s grace that moves in time with heaven, not the chaos of the calendar.

Grace for the Weary and Wounded

In times of loss, confusion, or fatigue, grace meets us quietly and consistently. It is:

- An antidote for anxiety

- A remedy for restlessness

- Decompression for depression

- Antivenom for sin

Grace is what saves us when we can’t save ourselves. It guides when we’re lost, comforts when we’re hurting, and encourages when the odds are stacked against us. It even carries us when we don’t know the way forward.

How Do We Learn These Rhythms?

- Come to Jesus—not just once, but daily

- Take his yoke—release the burdens you were never meant to carry alone

- Learn from him—observe his gentleness, humility, and wisdom

- Rest in him—receive the peace that only grace can give

This isn’t just self-care. It’s soul care. It’s a way of life Jesus modeled—and a way of life he still invites us to follow.

John Mark Comer reminds us, “Transformation is possible if we are willing to arrange our lives around the practices, rhythms, and truths that Jesus himself did, which will open our lives to God’s power to change.”

So today, let grace interrupt your hurry.

Let grace reframe your expectations.

Let grace teach you how to breathe again.

Because in Christ, we’re not called to hustle harder—we’re called to finish the race at the speed of grace.

(Barry Howard is a retired pastor who now serves as a leadership coach and consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches. He and his wife live on Cove Lake in northeast Alabama.)

(This post is a summary of a sermon I shared in 2023.)