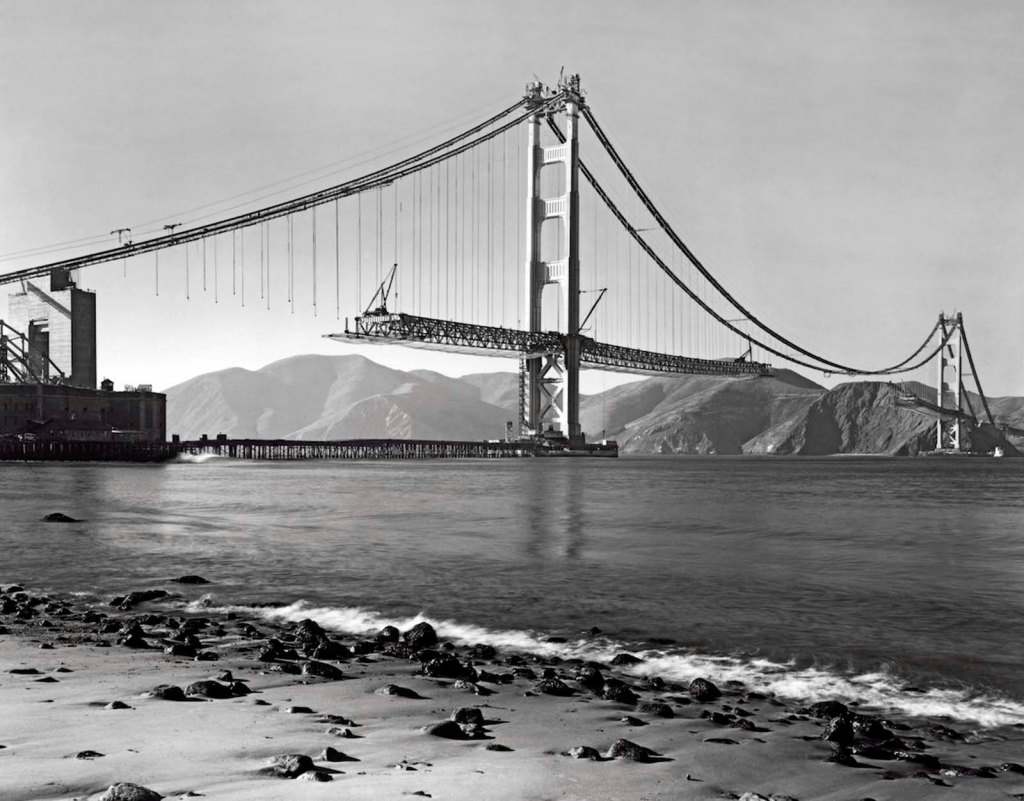

When construction began on the Golden Gate Bridge in 1933, skeptics said it couldn’t be done. The winds were too fierce. The fog too dense. The span too long. But through grit, innovation, and vision, workers united across trades and backgrounds to connect two shores that had long been separated. Against enormous odds, the bridge was completed in 1937 and still stands today. It is not just as an engineering marvel, but a symbol of what’s possible when people work together to span what divides them.

Our nation needs that kind of bridge-building again, not with steel and cables, but with courage, empathy, and dialogue.

We are living in a time when division feels more visible and more visceral than ever. Political debates become personal battles. Social media threads unravel into shouting matches. Families gather around dinner tables, uncertain about how to talk about the world without tearing each other apart.

We are, in many ways, a nation of silos, more comfortable in our echo chambers than in conversations that challenge us. But if we want to build a better future, we cannot afford to remain divided. The health of our democracy and the well-being of our families and communities depend on our ability to build bridges across the great divide.

A wise person once remarked, “Unity is not the absence of differences but the presence of mutual respect in the midst of them.”

Division is not new, but it has been amplified. Fueled by polarized media, ideological entrenchment, and the fast-paced spread of misinformation and disinformation, we’ve drifted into a mindset that sees those who disagree with us not as fellow citizens but as threats. That’s a dangerous place for any society to be.

As the late Senator John McCain once warned, “We weaken our greatness when we confuse patriotism with tribal rivalries that have sown resentment and hatred and violence across all the corners of the globe.” Civility isn’t cowardice. It’s a form of courage. And dialogue isn’t defeat; it’s a doorway to understanding.

After the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln worked not only to reunite the nation politically but to heal it relationally. When criticized for showing kindness to Confederate sympathizers, Lincoln replied, “Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?” His commitment to unity, even amidst deep division, laid a foundation for national healing, one conversation and one gesture at a time

Recently, I read about a local church and a nearby civic group who hosted a community roundtable with people from across the political spectrum. The conversation was slow and awkward at times, but also honest, respectful, and hopeful. Participants left not with total agreement, but with mutual appreciation and a shared desire to keep the conversation going.

That’s where healing begins: not in uniformity, but in humility and respect.

A shared future requires shared values. Most of us, regardless of political leanings, want similar things: safe communities, healthy families, meaningful work, a stable economy, and a sense of dignity and belonging for all people. When we begin with the values we hold in common, we can face what divides us with greater grace.

To live in unity does not require uniformity of thought, perspective, or conviction. It does require that we build on our common values, even when we don’t share the exact same viewpoint. Rick Warren wisely reminds us, “We don’t have to see eye to eye to walk hand in hand.”

The work of bridge-building is not glamorous. It won’t trend on social media. But it is deeply necessary. It happens in quiet conversations, in community service projects, in choosing curiosity over caricature.

If we want to leave a better world for our children and grandchildren, we must begin not by shouting louder, but by listening deeper. We must become savvy builders who construct bridges, cultivate relationships, and collaborate as problem-solvers. And we must dare to believe that across even the widest divide, bridges can still be built.

Let us be those who build them.

(Barry Howard is a retired pastor who now serves as a leadership coach and consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches. He and his wife live on Cove Lake in northeast Alabama.)