In the Christian tradition, the 12 days of Christmas are about much more than “a partridge in a pear tree.”

For many people, Christmas feels like a single day, or at most, a short season that ends as soon as the decorations come down and your playlist reverts back to your favorite non-holiday tunes.

Yet, in the Christian calendar, Christmas is not a moment to rush through, but a season in which we are invited to linger. That season is known as the Twelve Days of Christmas, or Christmastide, stretching from Christmas Day (December 25) to Epiphany (January 6).

Rather than counting down to Christmas, the Church has long counted from it, by designating twelve days set aside to savor the mystery that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14).

The practice of observing the Twelve Days of Christmas dates back to the early centuries of the Church. By the fourth century, Christmas and Epiphany were firmly established as interconnected feasts celebrating the incarnation of Christ and the revelation of that incarnation to the world. While Epiphany would later emphasize the visit of the Magi, Christmastide underscored the themes of birth, light, revelation, and joy.

In medieval Europe, these twelve days were marked by worship, feasting, storytelling, music, and rest. Work slowed. Communities gathered. The world itself seemed to pause long enough for people to absorb the wonder of Christmas. The Twelfth Night was often celebrated with special services, candles, and communal meals, signaling both joy and transition.

In the Christmas décor displayed in our home, we have a collection of quaint English villages. These not on remind us of the scenes in Dickens’ Christmas Carol; they also hark back to the Middle Ages when homes in English Villages kept Yule logs burning throughout the twelve days, symbolizing the enduring light of Christ in the darkest season of the year.

Christmastide invites us to live into the truth announced on Christmas Eve: “Unto us a child is born” (Isaiah 9:6). The season is not about adding more festivities but about allowing the significance of Christ’s birth to settle into our hearts.

The Twelve Days remind us that joy deepens when it is not rushed. Christmas is not meant to be consumed in a day but contemplated over time.

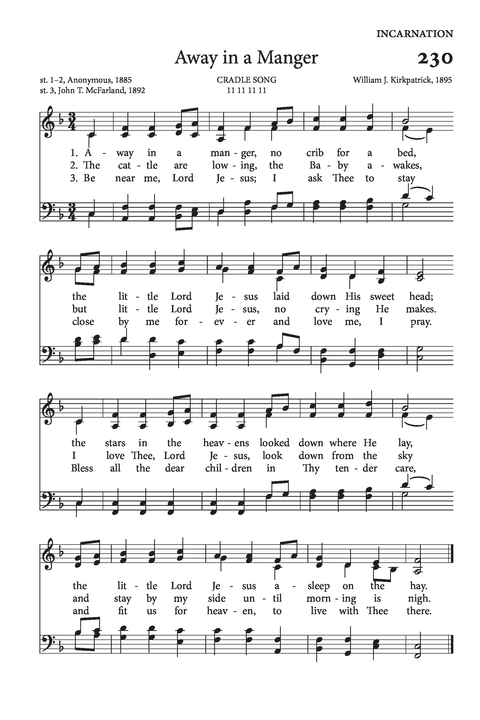

The familiar carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas” has often been misunderstood as a playful take on holiday gifts. While symbolic interpretations of the gifts mentioned in the carol are often debated, the song itself reflects the spirit of Christmastide. It echoes a season where joy accumulates progressively.

As theologian Frederick Buechner once wrote, “Joy is what happens to us when we allow ourselves to recognize how good things really are.” Christmastide creates space for that recognition.

The Twelve Days of Christmas culminate in Epiphany, the celebration of the Magi’s visit to the Christ child. This moment widens the lens of Christmas, reminding us that the child born in Bethlehem is not only for a small family or a single nation, but for the whole world.

Matthew 2:11 tells us, “They saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage.” The journey of the Magi signals that Christmas leads us outward from adoration to action, from wonder to witness.

Historically, Epiphany was one of the most important feast days of the year, especially in Eastern Christianity, emphasizing revelation and light. In many cultures, gifts were exchanged on January 6 rather than December 25, underscoring that the Christmas story unfolds over time.

In a culture that urges us to move on, Christmastide invites us to stay. To keep the tree lit a little longer. To sing carols past December 25. To practice gratitude after the gifts are opened. To let peace settle in once the rush subsides.

As Howard Thurman wisely observed, “When the song of the angels is stilled… the work of Christmas begins.”

The Twelve Days of Christmas remind us that Christmas is not an ending but a beginning. Christmastide invites us to experience the joy and explore the wonder that “the Word became flesh and moved into the neighborhood” (John 1:14 The Message).