C.S. Lewis proposed, “In Christianity God is not a static thing … but a dynamic, pulsating activity, a life, almost a kind of drama — almost, if you will not think me irreverent, a kind of dance.”

Every year, the first Sunday after Pentecost invites Christians to linger over the greatest known unknown of the faith: God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In the church of my upbringing, as we affirmed the holiness of God, we sang, “God in three persons, blessed Trinity!”

1. The word Trinity never appears in Scripture, yet the biblical story keeps naming a tri-personal God who creates, redeems, and indwells the world. The pattern of God’s threefold nature emerges from the core of the biblical message:

- At creation, God speaks the world into being, the Spirit hovers over the waters, and together they bring life (Gen 1:1–2, 26).

- At Jesus’ baptism, the heavens open, the Father speaks, the Spirit descends, and the Son stands in the water—an unmistakable picture of divine community (Matt 3:16–17).

- At the Great Commission, Jesus sends his followers out in the name—not names—of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Matt 28:19).

So while the term came later, the concept of a triune God was there from the beginning.

2. From the beginning, God is introduced as intra-communal in nature. Genesis does more than recount cosmic origins; it unveils a God who is relationship itself. Before mountains were sculpted or stars ignited, Father, Son, and Spirit shared eternal fellowship. Theologian Cornelius Plantinga once put it this way: “The persons within God exalt each other, commune with each other, and defer to one another. Each harbors the others at the center of their being.” In other words, God is a perfect community of mutual love and unity.

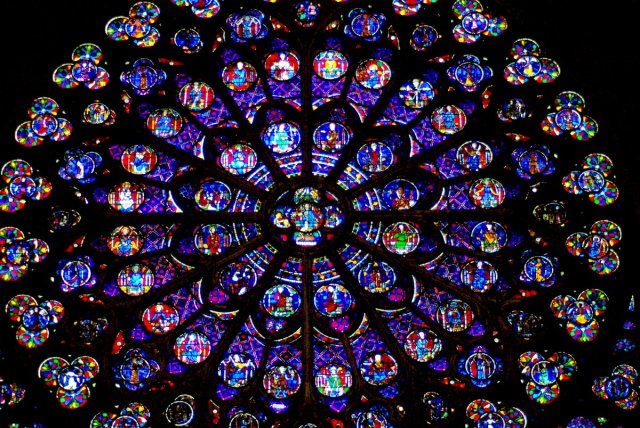

3. Metaphors give us a point of reference for the Trinity but are insufficient to fully capture the essence of God’s being. Stories help us speak about the unspeakable, yet every image has limits. Saint Patrick, so legend says, plucked a shamrock to illustrate “three in one” for the Irish clans. It was a winsome start, but the plant cannot convey the depth of divine personhood. Water (steam, liquid, ice) risks modalism; the sun (star, light, heat) flirts with subordinationism. Good metaphors open doors; they are not blueprints of the mystery.

4. The Trinity is best contemplated in the rich diversity of perspectives, not a singularly authoritative definition. Western theology tends to speak of one essence in three persons (think Augustine and the Athanasian Creed); Eastern writers prefer the word perichoresis—an eternal, mutual inter-dwelling. Both vocabularies circle the same fire from different sides.

5. The persons of the Trinity have different roles but one mission. Since the notion of Trinity refers to the intra-communal nature of God, the roles and objectives assumed by the members of the Trinity do not counter of contradict the other. Within the Trinity, the Father creates, the Son redeems, and the Spirit empowers, but they are never in conflict. Every movement of God throughout history flows from one divine source, with each person of the Trinity working in perfect harmony toward the restoration of all things.

In his book, Thinking About God: An Introduction to Christian Theology, Fisher Humphreys concludes his chapter on the Trinity with this summary:

In some wonderful and mysterious way, the one, true, living God is eternally Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These Three Persons live a life of knowing and being known, of speaking and listening, of trusting and being trusted, of loving and being loved. As astonishing as it may seem, we human beings are called to share in their eternal life. We have already begun to share in the love of the Father, Son, and Spirit, and we will be enfolded in their life and love throughout eternity.

Trinity Sunday is about recognizing that the deepest truths of God are relational, mysterious, and gloriously beyond containment. The Trinity is not a diagram to be drawn, but a mystery to be received.

Let us dance with that mystery, even though we cannot fully comprehend the choreography.

(Barry Howard is a retired pastor who now serves as a leadership coach and consultant with the Center for Healthy Churches. He and his wife live on Cove Lake in northeast Alabama.)